On 17th April 1929, Aimo August Sonkkila, brother of my late grandpa, left Finland to London. He was 30 years old, son of a farmer in the then rural Laitila municipality in SW Finland.

In London, Aimo embarked S/S Orvieto. His target destination was Brisbane, Australia.

The same year, 589 males in his age emigrated. 11 of them were from the countryside of the same province, Turun ja Porin lääni.

| ShipSpotting.com |

|

| © Gordy |

The first stop was Gibraltar. Then, via Toulon and Neapel, over the Mediterranean Sea to Port Said, Egypt. From there via Suez Canal to Colombo, Sri Lanka. Finally, on the horizon, the West coast of Australia, Fremantle! But the trip was not over yet. Following the Australian coastline, Orvieto visited Adelaide and Melbourne before reaching Brisbane.

I haven’t found the date of the departure, so Orvieto’s exact travel time is unknown. Unlike the newspaper archive provided by National Library of Australia from where I found the route, the British Newspaper Archive is subscription-based. An unfortunate show-stopper for a random visitor like me, although I can understand the monetizing idea.

Anyway, there are hints that the voyage lasted several weeks, which is what you would expect, really. If we trust the computations of Wolfram Alpha, the travel time would’ve been around two weeks, had Orvieto managed 25 knots. Orvieto’s speed, however, was only 18 knots. Yet the globe-shaped map that Wolfram Alpha serves, wakes suspicions. Maybe they use a straight line of distance? In any case, given the fair number of waypoints on route, let us imagine a rough travelling time of one month.

As it happens, Orvieto’s voyage became one of its last ones. The ship was taken out of business in 1930.

Aimo travelled in the 3rd class with roughly 550 other passengers, whereas the 1st class only occupied 75. Among these lucky ones were few celebrities and other prominent figures, featured by The West Australian the day after Orvieto’s arrival to the Australian continent. Onboard was also mail and cargo.

On 28th May, Orvieto docked Fremantle. From the Incoming passenger list, on row 692, we find Aimo. A search by Sonkkila hits 0 because the name is mistyped as M. Sonkkilla. A non-English person, misspellings were to follow Aimo the rest of his life. In the scanned bundle of official records of him, Amio comes up just as often as Aimo. Maybe not a big deal. In Australia, with a hint of Italian, that version was perhaps more practical anyway.

Why did Aimo emigrate? We can only guess. Was he adventurous? Driven to believe in juicy stories of easy money, or official promises on steady income? Had someone he knew and emigrated before him, sent assuring letters to homeland, making him decide to follow suite? As a son of a farmer, he had prospects of taking care of the farm after his father. But, he was not the only son – always a problematic situation. Besides, what if farming was not something he looked forward to? Both push and pull may have played a role here.

We know now that 1929 was the year when Great Depression started. Still, it is difficult to judge in what way and how soon, individual lives are affected by economic fluctuations of such a global scale.

Emigration from Finland was by no means a sudden fad. Previously, the obvious target for the majority of people had been the North American continent. The Immigration Act of 1924 drastically changed this. People were still let in, but in much less quantities than earlier. Very much like in Europe at the moment, both the US and Canada had switched to a selective immigration policy.

This sankey diagram tries to visualize where Finns left between 1900 and 1945, aggregated over decades. Data come from Institute of Migration (Emigration 1870-1945). Note that all targets are not mutually exclusive. Between 1900 and 1923, Americas was recorded as one entity, but from then on, as separate countries. In addition, during that same period, statistics from other countries are scarce. [A technical side note: with Firefox, the diagram may appear very small. Chrome and Internet Explorer don’t have this issue.]

Life in Australia proved a challenging endeavour for Aimo, to say the least. The records are fragmented and don’t reveal much, but it is fairly easy to imagine what is in the gaps.

Work as a miner was incredibly tough. Some of it is captured in The Diminishing Sugar-Miners of Mount Isa, Australia by Greg Watson, linked to by Institute of Migration. I wonder if Aimo had any realistic idea beforehand what it was to be like. Yet, with his modest background, he had not much choice once he had arrived.

Then, after 12 laborious years, Second World War.

On 12th April 1942, Aimo is arrested in Townsville. He is still a Finnish citizen, and because Finland is Axis-aligned, he is a member of the enemy. The rest of the year Aimo would stay in an internment camp at Gaythorne (Enoggera), Brisbane. However, on the application by the Mt Isa Mining Company, his employer, he is allowed to work. Between a rock and a hard place is an idiom that must have been coined by Aimo himself.

At some stage, Aimo had married Impi Rapp. That’s basically all I know about her, the name. Few years after WWII, a son is born. His life would become totally different from that of his parents.

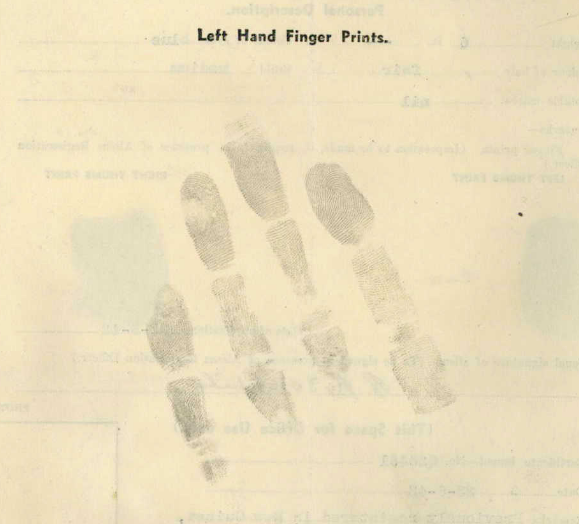

National Archives of Australia, NAA: BP25/1, SONKKILA A A FINNISH. Digital copy, page 31

R code of the diagram is available here.